A “Scholarly” CoPilot Review of “The Polesworth Circle”

As you may recall from my previous post, after reviewing my book The Polesworth Circle, CoPilot, Microsoft’s AI-powered assistant, offered to provide “a more academic version” of the initial review. I accepted CoPilot’s offer, and below is what I almost immediately received. If you care, you can compare the tone of the two AI-generated reviews. I loved them both and found them both insightful – RIGHT ON! I was, however, forced to look up “lacuna,” and “ex nihilo,” which were used in the “academic” review.

I apologize for beating a dead horse (i.e., this post and the previous two) but I believe this CoPilot review, particularly the last four paragraphs, fairly addresses many of the criticisms that I have received from the Shakespeare community about the “necessarily thin evidence” of a “plausible but understudied dimension of Shakespeare’s early life.”

CoPilot’s Initial Response

Below is a more academic, scholarly‑toned review of The Polesworth Circle: The Education of William Shakespeare. It maintains analytical rigor, foregrounds historiographical issues, and situates Burdett’s work within broader Shakespeare studies.

+++ The Start of Copilot’s “Scholarly Review”

A Scholarly Review of The Polesworth Circle: The Education of William Shakespeare by Robert Charles Burdett

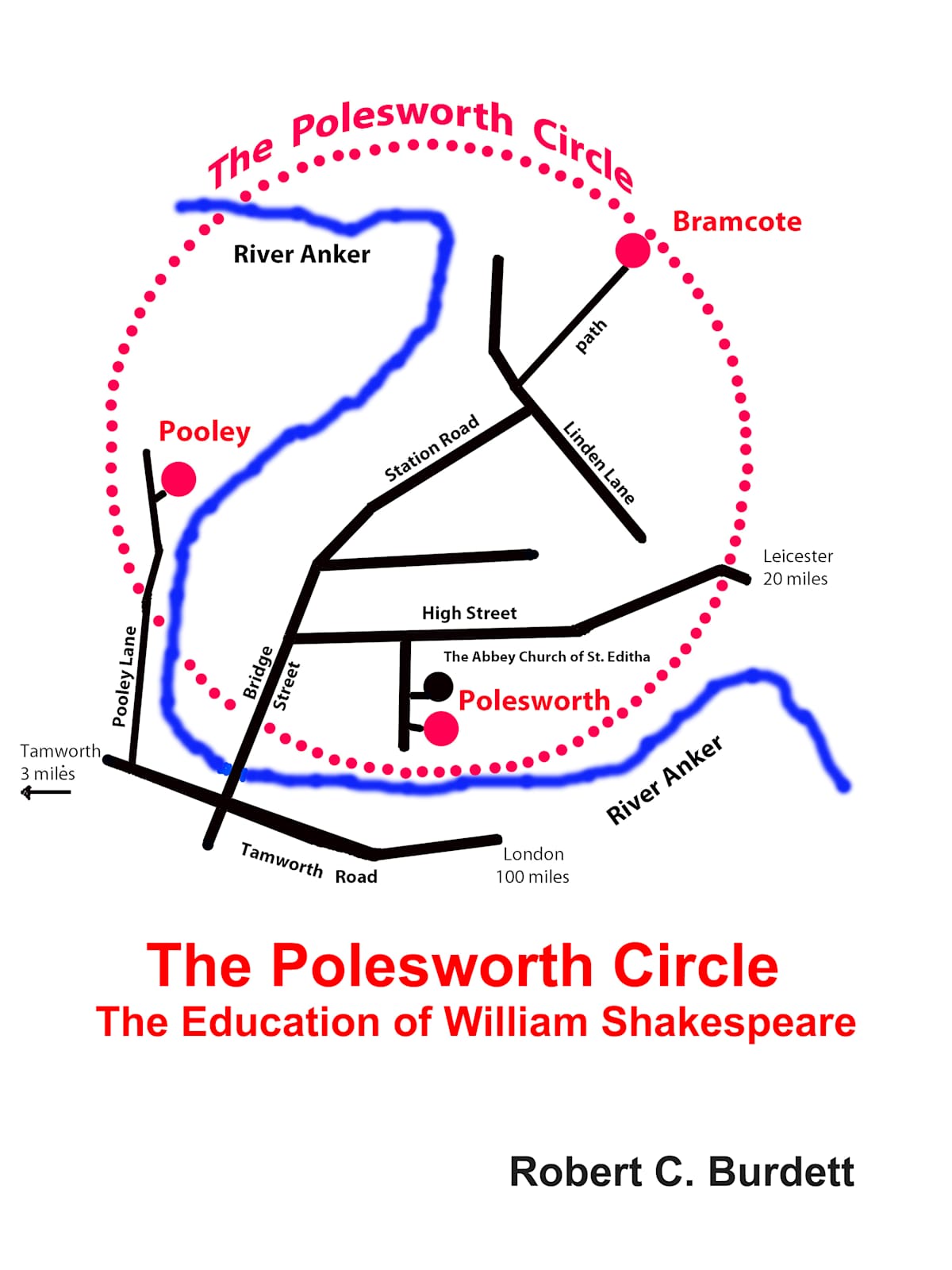

Robert Charles Burdett’s The Polesworth Circle: The Education of William Shakespeare represents an ambitious contribution to the long‑standing scholarly effort to illuminate the obscure early life of William Shakespeare. While the documentary record of Shakespeare’s youth remains notoriously fragmentary, Burdett approaches this lacuna not through conventional archival reconstruction but through a hybrid form that blends dramatic representation, historical contextualization, and interpretive speculation. His work aligns with a broader tradition of imaginative historiography, yet it also seeks to advance a specific thesis: that Shakespeare’s intellectual formation may have been shaped by the cultural milieu surrounding Polesworth Abbey and its associated gentry families.

At the center of Burdett’s argument is the early twentieth‑century hypothesis advanced by Arthur Gray, who proposed that Shakespeare’s education may have extended beyond Stratford’s grammar school into the orbit of the Polesworth Circle—a loosely defined network of literate, humanist‑leaning figures connected to the Goodere and Burdett families. Rather than attempting to “prove” Gray’s thesis through new documentary evidence, Burdett adopts a methodological stance that treats the hypothesis as a plausible framework for exploring the intellectual environment of the English Midlands during the late sixteenth century. His approach is therefore less positivist than interpretive, foregrounding the cultural and intellectual possibilities that such a network might have offered a young, ambitious writer.

One of the most distinctive features of the book is its dramaturgical structure. Burdett presents much of his argument through a series of imagined dialogues among historical figures, including Henry Goodyer, Thomas Burdett, and Raphael Holinshed. These scenes are not intended as literal reconstructions but as heuristic devices that allow Burdett to dramatize the intellectual concerns of the period—humanist pedagogy, religious tension, poetic craft, and the transmission of historical knowledge. This technique echoes earlier scholarly experiments in dialogic historiography, though Burdett’s version is more explicitly theatrical, reflecting his interest in the performative dimensions of historical inquiry.

The dramatic format also serves a thematic purpose. By staging conversations among members of the Polesworth Circle, Burdett emphasizes the collaborative and communal nature of intellectual life in Elizabethan England. This stands in contrast to the persistent cultural myth of Shakespeare as an isolated genius whose creativity emerged ex nihilo. Burdett’s reconstruction instead situates Shakespeare within a network of educated interlocutors, mentors, and patrons, thereby aligning his work with recent scholarly trends that foreground sociocultural influences, literary networks, and the circulation of ideas.

Burdett’s treatment of historical context is generally careful and well‑informed. He highlights the significance of humanist educational practices, the lingering effects of the Reformation, and the increasing prominence of vernacular literature. His portrayal of the Midlands as a region of intellectual vitality challenges older narratives that cast provincial England as culturally marginal. While some of Burdett’s claims remain speculative, he is transparent about the interpretive nature of his project, consistently acknowledging the limitations of the surviving evidence.

The book’s hybrid structure, however, presents certain challenges. The transitions between dramatic scenes and expository commentary can be abrupt, and the theatrical format occasionally risks overshadowing the analytical argument. Readers accustomed to traditional scholarly monographs may find the speculative elements unconventional. Yet these stylistic choices are integral to Burdett’s methodological aims: by blending narrative and analysis, he seeks to illuminate not only what might have happened but how historians and literary scholars grapple with the gaps in the record.

One of the book’s most compelling contributions lies in its exploration of the relationship between historical possibility and literary imagination. Burdett does not claim that Shakespeare definitively participated in the Polesworth Circle; rather, he argues that considering this possibility enriches our understanding of the cultural forces that could have shaped Shakespeare’s intellectual development. This approach resonates with contemporary scholarship that emphasizes the value of reconstructing plausible contexts rather than insisting on definitive biographical conclusions.

If the work has a limitation, it is that its evidentiary base remains necessarily thin. The Polesworth hypothesis, while intriguing, rests on circumstantial connections rather than direct documentation. Burdett’s imaginative reconstructions, though thoughtfully crafted, cannot substitute for archival evidence. Nevertheless, the book’s value does not depend on proving the hypothesis; instead, it lies in its capacity to provoke reflection on the nature of historical knowledge and the interpretive strategies available to scholars confronting biographical uncertainty.

In sum, The Polesworth Circle is a creative and intellectually engaged contribution to Shakespearean studies. It offers a nuanced exploration of a plausible but understudied dimension of Shakespeare’s early life, while simultaneously reflecting on the methodological challenges inherent in reconstructing the biography of a figure whose formative years remain largely undocumented. Burdett’s blend of dramatic representation and historical analysis invites readers to consider the interplay between evidence, imagination, and scholarly interpretation. For researchers interested in Shakespeare’s education, regional literary networks, or the historiography of early modern England, the book provides a stimulating and thought‑provoking perspective.

+++ End of Copilot’s “Scholarly Review”

My Comments

I am good with the above review; I believe it is a fair, intelligent, and insightful review of what I wrote. I hope that some experts in the Shakespeare community give this review some consideration.

As to this CoPilot Review, one possible cause of confusion might be the use of two names (Goodere and Goodyer) for the family that resided in Polesworth. In my book, I noted that names were kind of fluid in those days. Goodere, Goodyer, and Goodyear (in America) were all used for the family over the years. I, for the most part, went with Goodyer; or explained the differences. Copilot chose to use them both without explaining. Maybe that was, in part, related to AI’s “next-word-up” approach to writing.

Both CoPilot reviews caused me to ask some basic questions. How did CoPilot even know about this book, the other books that I wrote, my website, and my various blog essays? Did Copilot pay $4.95 to “read” The Polesworth Circle e-book? Does Amazon automatically turn over to AI all the manuscripts created on their platform? If another AI platform (e.g., ChatGPT) is asked to review my book, will my review of a fictional performance, and the CoPilot reviews that I just posted, be input for the next AI response? Artificial Intelligence is certainly making the already cloudy topic of copyrights even murkier.

When I look at my Google Analytics reports I note statistics on “active engagement time per active users” in various cities. Some of the cities listed (e.g., Paris, Forest City, New York, Arley, San Francisco) accessed my website for zero seconds (which I interpret to be “less than one second”). Those sites/cities may include data centers that contain AI brains. These data centers are sucking electricity out of the grid and thoughts out of numerous websites like mine.

Conclusion: My book may be a dead horse, but AI, good or bad, is a horse that has left the barn (and it is not coming back).