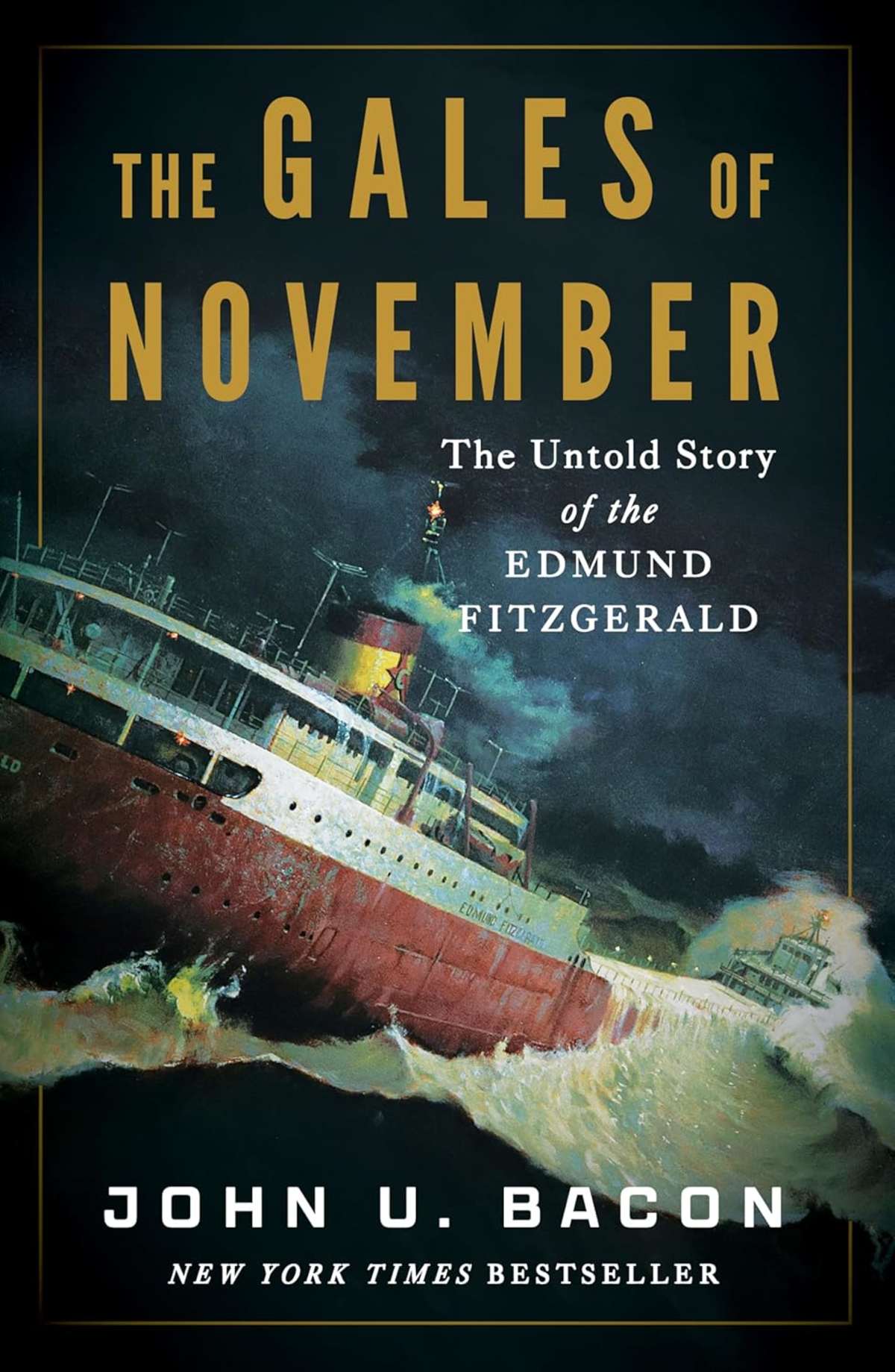

During my recent Florida vacation, I read two books. The second was The Gales of November: The Untold Story of the Edmund Fitzgerald by John U. Bacon (copyright 2025). In this review, [brackets] are used to denote the pages from his book where the various quotes were obtained.

I previously described my fascination with the Great Lakes, the big freighters that ply them, and the Edmund Fitzgerald in particular, in my previous blog entries – A Michigan Vacation (October 10, 2025) and The “Edmund Fitzgerald” (October 25, 2025). I suspect that is why I was attracted to Bacon’s book.

In my October 25 post I wrote about the Edmund Fitzgerald sinking. But other than noting that the ship sank during a storm, I never addressed the specifics of why the ship went down. Why, for example, did the Fitzgerald sink and the Arthur M. Anderson, which was following a similar route at about the same time, survive? That is the “untold story” that Bacon addressed and I was interested in.

Coincidently, as I was reading this book, as 2025 was coming to an end, another huge storm was ravaging the Great Lakes – comparable to the storm that ravaged the lakes in 1913, and the storm that sank the Edmund Fitzgerald in 1975 (more later).

My Facebook and X algorithms have both detected my interest in the big freighters and the Great Lakes. Over the last few weeks, I have been inundated with videos of the big freighters working their way through the locks and lakes; and statistics on the winds and waves ravaging the Great Lakes.

Early in his book, Bacon frames the setting of his book by noting: “When Alex de Tocqueville, the Parisian aristocrat and polymath, traveled to the United Sates in the 1830s to write his famed treatise, Democracy in America, he was awestruck by the Great Lakes. ‘This lake without sails, this shore which does not yet show any trace of the passage of man, this eternal forest which borders it; all that, I assure you, is not grand in poetry alone; it’s the most extraordinary spectacle that I have seen in my life’ [7-8].”

There are two major parts to Bacon’s book involving – the physical (e.g., the lakes, waves, ships, ports, locks) and the personal (e.g., the captain, his crew, and the others affected by the tragedy). I will primarily address the physical parts of Bacon’s book in this review.

A Correction

First, let me make a correction to my October 25th post. In that post I wrote, “Ice formations on these fresh-water Great Lakes close the Sault St. Marie locks every winter, and there is always pressure to get one more load of taconite or grain through the locks before the shipping season ends.” The statement, as written, is true but, via context, it implied that the Edmund Fitzgerald’s passage that November was late in the shipping season.

· In actuality, this was the Edmund Fitzgerald’s last scheduled trip on Lake Superior, as it was scheduled for season ending repairs in Toledo, starting in mid-November.

· In actuality, the Great Lakes' shipping season usually extends into mid-January, until ice clogs the Soo Locks at Sault St. Marie.

· Thus, while there may be pressure to “push” the shipping season, it comes in late December and early January, not during November.

The 2025-26 Great Lakes' shipping season ended on January 15, 2026. A 1000-foot freighter called American Spirit was the last ship to pass through the Soo Locks, taking three hours because of heavy ice. The Soo Locks will remain closed for maintenance until March 25, 2026.

The Gales of November Historically

Bacon notes that November is historically a very dangerous time on the Great Lakes – maybe more so than December or early January.

In two early chapters, The Storm of the Century, 1913 and The Bureau of Lost Souls, Bacon reports on the “White Hurricane” that ravaged the Great Lakes in mid-November 1913. He writes, “… the best estimates tell us the juggernaut wiped out a staggering nineteen ships, with 254 people aboard. … They called it the Storm of the Century … until November 10, 1975 – just enough time for the painful lessons of 1913 to be forgotten” [27-28]. Bacon also describes the November storms that ravaged the Great Lakes' freighters in 1930 and 1958.

Per Bacon and his sources, the November storms are more dreaded and dangerous because the air-lake temperature differences in November are huge (versus December); and the storms moderate (during December) as the winter snows accumulate.

The Ships Versus the Waves

Per John Tanner, the former superintendent of the Great Lakes Maritime Academy, “The word ‘lake’ doesn’t do them justice. People on the coasts don’t get it. The Great Lakes don’t behave like lakes. They function more like seas, big enough to develop waves, which grow as they cross the lakes” [8].

In an early chapter entitled A Higher Degree of Danger, Bacon does a good job of noting the differences between the waves on saltwater oceans and the waves on freshwater lakes.

“On the Great Lakes there’s no salt to hold down the waves, so they rise more sharply and travel closer together … These waves don’t roll; they peak, crest, then crash down on whatever is unlucky enough to lie below them” [8].

“On the ocean the waves are usually about ten to sixteen seconds apart … On Lake Superior the waves run four to eight seconds apart, which means that a seven-hundred-foot lake freighter can be riding atop two waves at once [which is called “hogging”]. … A ship fighting through a serious storm can get caught in a harrowing cycle of hogging and sagging every few seconds” [9].

Bacon also describes a statistical function named the “Raleigh Distribution” and how it relates to maximum wave heights. Waves of 25 feet are not uncommon during major storms. Per the Raleigh Distribution, if the waves that the Fitzgerald encountered, as it crossed the east coast of Lake Superior, were 25 feet tall; they probably encountered ten 47-foot waves and possibly a sixty-foot rogue wave.

The oddly shaped Great Lakes' freighters are designed to maximize profits and fit through the various locks but they are “… poorly designed for smooth sailing in rough waters: too flat on the bottom to avoid rolling in heavy seas, so low to the water they are easily buried by big waves, and so long and thin they risk cracking in between the waves when fully loaded” [50]. In short, they are not designed for the storms of a century.

Bacon, in a chapter entitled Cheating the Plimsoll Line, describes how, over time, the maritime authorities allowed more cargo to be loaded into ships’ cargo holds, which results in the freighters sinking further into the water. He also notes how the boat operators could stretch the rules (“cheat”) to maximize their loads to levels that were not envisioned by the boat architects.

All the above impacted the Edmund Fitzgerald on its last cruise.

The Soo Locks

In a chapter entitled The Bottleneck, Bacon presented a good overview of Whitefish Bay and the history of the Soo Locks at Sault Ste. Marie. Bacon noted how the Army Corps of Engineers worked feverishly to complete the locks in 1943 – to support the war effort. He also noted that seven thousand soldiers were stationed by the locks, and “barrage balloons” were deployed to protect the locks from an aerial attack. The quote that wowed me was, “If the Poe Lock went out of order for just six months, it would cost the U.S. economy eleven million jobs” [133].

The Sailors Say “Brandy”

In my October 25 post I wrote about Gordon Lightfoot’s great ballad – The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald. In a chapter entitled Life on Shore, Bacon noted that the Great Lakes' sailors hummed and sang a different song at the port bars that offered cheap beers and a jukebox. Thousands of quarters were spent to hear a song loved above all others – Brandy (You’re a Fine Girl).

The sailors say, “Brandy, you’re a fine girl

What a good wife you would be

But my life, my love, and my lady is the sea

That song was popular, in part, because it reflected the lonely life of the sailors working on the Great Lakes' freighters. Many wives and girlfriends were left at port because their lady was the sea. The sailors’ lives revolved around the rhythm of the ships – from the mines to the steel mills – between the shipping and off seasons.

The Start of the Fateful Trip

Bacon spent a lot of pages setting the table. It was not until Section XII, on page 235, that he wrote One Last Run (November 8-10, 1975).

Bacon’s account reminded me of how much more precise weather forecasting is today than it was in 1975. The forecasts back then were not nearly as precise (timing, path, duration, intensity) as they are today. This lack of precise information impacted the ship’s captains and led to some decisions that, in hindsight, could best be described as bad.

In the paragraphs below, I will summarize the material that Bacon wrote about in Section XII:

On November 8, 1975, the captain of the Edmund Fitzgerald had to make three decisions: whether to sail, which route to take, and how fast to go. His initial decision to sail was probably a given – in those days captains sailed. The ship owners would be asking questions if their cargos were delayed. It should be noted, however, that the Sykes, which had departed port about the same time, later pulled into nearby Thunder Bay for safe harbor. The Sykes is still sailing the Great Lakes, fifty years later.

The captain’s initial decision to take the normal, more direct, and fastest route was probably the best – but he changed his mind shortly after sailing. Instead, he switched to the “safer,” more protected, northern route – but that added fourteen hours to the cruise. He also lowered his speed at times, which, again in hindsight, prevented him from getting ahead of the storm.

The above decisions eventually put him in the worst place at the wrong time – going south towards Whitefish Bay with huge waves rolling across his ship on the starboard side. The ship had left port with thousands of tons more taconite than her architects had designed her to carry – leaving her only 11.5 feet of freeboard (compared to the 25-foot routine waves and any 60-foot rogue waves that she might come upon).

In a chapter entitled Fitzgerald’s Cousin, Bacon describes the interactions and communications between the Fitzgerald and the Arthur M. Anderson, as those two ships took essentially (with one major exception, to be discussed later) the same route across Lake Superior.

The End of the Fateful Trip

A lot of things could have caused or contributed to the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald. Bacon writes of many of these factors (e.g., the design of the ship itself, damaged cover hatches, record waves, motion fatigue and navigational errors).

The Arthur M. Anderson received several reports from the Edmund Fitzgerald as they approached Whitefish Bay (“I have sustained some topside damage. I have a fence rail laid down, two vents lost, or damaged and a list. I’m checking down (slowing).” … [and later] “I have a bad list, lost both radars. And am taking heavy seas over the deck. One of the worst seas I’ve ever been in”).

From the above, Bacon presents a case (but does not absolutely state) that the Fitzgerald ultimately sank because of a navigation error – the grounding of the ship’s hull when it ran directly over Six Fathom Shoal.

Six Fathom Shoal

A map in Bacon’s book depicts the routes of the Edmund Fitzgerald and the Arthur M. Anderson across Lake Superior. The routes were similar until the ships started heading to the southeast. The routes of the two ships changed drastically around Caribou Island – the Anderson sailed well north and then well east of the island. The Fitzgerald sailed more diagonally just to the east of the island (over or very near Six Fathom Shoal). Bacon notes that “… in some places it’s a mere eleven feet below the surface …” [274].

Bacon noted that, by choosing to take the northern route, the Anderson and Fitzgerald captains were taking a route that they seldom took – a route that they were not very familiar with – and a route in which the navigation charts were incorrect. “In 1976 the Canadian Hydrological Service surveyed Six Fathom Shoal and found that it actually ran about one mile farther east than indicated by the chart McSorley was using” [275].

“… the Great Lakes’ top nautical investigator, Dick Race [reportedly told three friends] … On the hard bedrock of Six Fathom Shoal he found the Fitzgerald’s distinctive maroon paint, still clearly visible and embedded in the stone about six months after it sank.” … he told those three friends that he believed the Fitzgerald had bottomed out on the shoals and damaged its hull, which allowed water to rush in, creating the starboard list McSorley complained about [343].

Per this theory, the Fitzgerald struggled along towards Whitefish Bay, taking on water, until she drove her bow into a wave – and then she went down fast (no time for lifeboats and radio messages). The captain’s clues (fence rail down, worsening list) support this “grounding” theory.

The Ballad

Towards the end of the book, in a chapter entitled The Ballad, Bacon wrote about the events (e.g., news reports) that led Gordon Lightfoot to write his famous ballad. Per Bacon, “The version people have been hearing on the radio for decades is actually the first time the band ever played the song” [360].

Apparently, Lightfoot had worked on the song by himself and was somewhat reluctant to record it. When some studio time opened up at the last minute, he agreed to give it a shot. None of the band had ever heard the whole song so, at times, they just played what they felt. Lightfoot told the drummer to come in when he nodded. At the end of second verse, Lightfoot nodded, and the drummer came in with a strong tom fill to mimic a storm crashing down. Lightfoot and the band tried to improve on the first take, but Lightfoot eventually decided to go with the first take.

My Review

I enjoyed the book; I learned a lot of things about the Great Lakes' shipping industry. Bacon chose to incorporate the stories of the crew into the ship’s tale. Pages 147-226 told their stories and then Bacon referred to them – and their survivors – after their deaths. As such, prepare to slog through these stories if you, like me, are more interested in the details of the ship’s demise than the human aspects of the story.

The Gales of December – 2025

As I noted at the start of this review, another “storm of the century” struck the Great Lakes at the end of December 2025. Maybe this is another result of “global warming.” The lake temperatures remain warm longer and later – November is becoming December.

In any case, the Great Lakes' shipping industry seems to be much more prepared for such storms, according to my X and Facebook posts. Now, the weather forecasts are much better and more precise. The relatively crude radars of 1975 have been replaced by better navigation and GPS equipment. The ships now know more precisely where they are and what is around them. Now ships get ahead of the weather or shelter until the storms pass.

On Saturday, December 27, I noted a tweet reporting that, “Waves are expected to be larger on Lake Superior this Monday than what took down the Edmund Fitzgerald over 50 years ago. … The latest marine forecast from the National Weather Service [predicts that] … Waves are expected to reach 34 feet on Lake Superior ….”

On Sunday, December 28, I noted a tweet reporting that; “The last bulk freighter on the open waters of Lake Superior Sunday evening is the 730-foot American Mariner that left Marquette, MI bound for port in Toledo, OH ahead of the incoming “Bomb Cyclone”! The vessel is chugging safely around Whitefish point toward the Soo Locks less than 12 hours ahead of waves that may build to 30 FEET by Monday morning in Lake Superior.”

On Monday, December 29, I noted a tweet reporting: “CLOSED FOR BUSINESS: Strong winds and dangerous waves have completely shut down marine traffic on the Great Lakes this evening. Not a single vessel is taking the risk on the open water.”

On Tuesday, December 30, I noted the following tweet: “SAFE HARBOR | … [The American Mariner] remains safely in harbor on the St. Mary’s River after smoothly passing through the Soo Locks. It has been waiting out 20+ foot seas on Lake Huron over the past 24 hours before resuming the trip. ….”

On Friday, January 2, I noted the following tweet: “The 730-foot American Mariner has safely arrived in Toledo! … A few days delayed due to the storm, but welcome and Happy New Year!”

Note: On September 2, 2025, as my wife and I were completing our Soo Locks Boat Tour, we passed the west bound American Mariner. The ship replied to our boat’s hello (long-short-short) and two crew members on the bow of the ship waved to us. A picture taken at that time is shown below. Those sailors have now completed the 2025-6 shipping season. They are alive and hopefully resting on shore – getting ready for the 2026-7 shipping season.