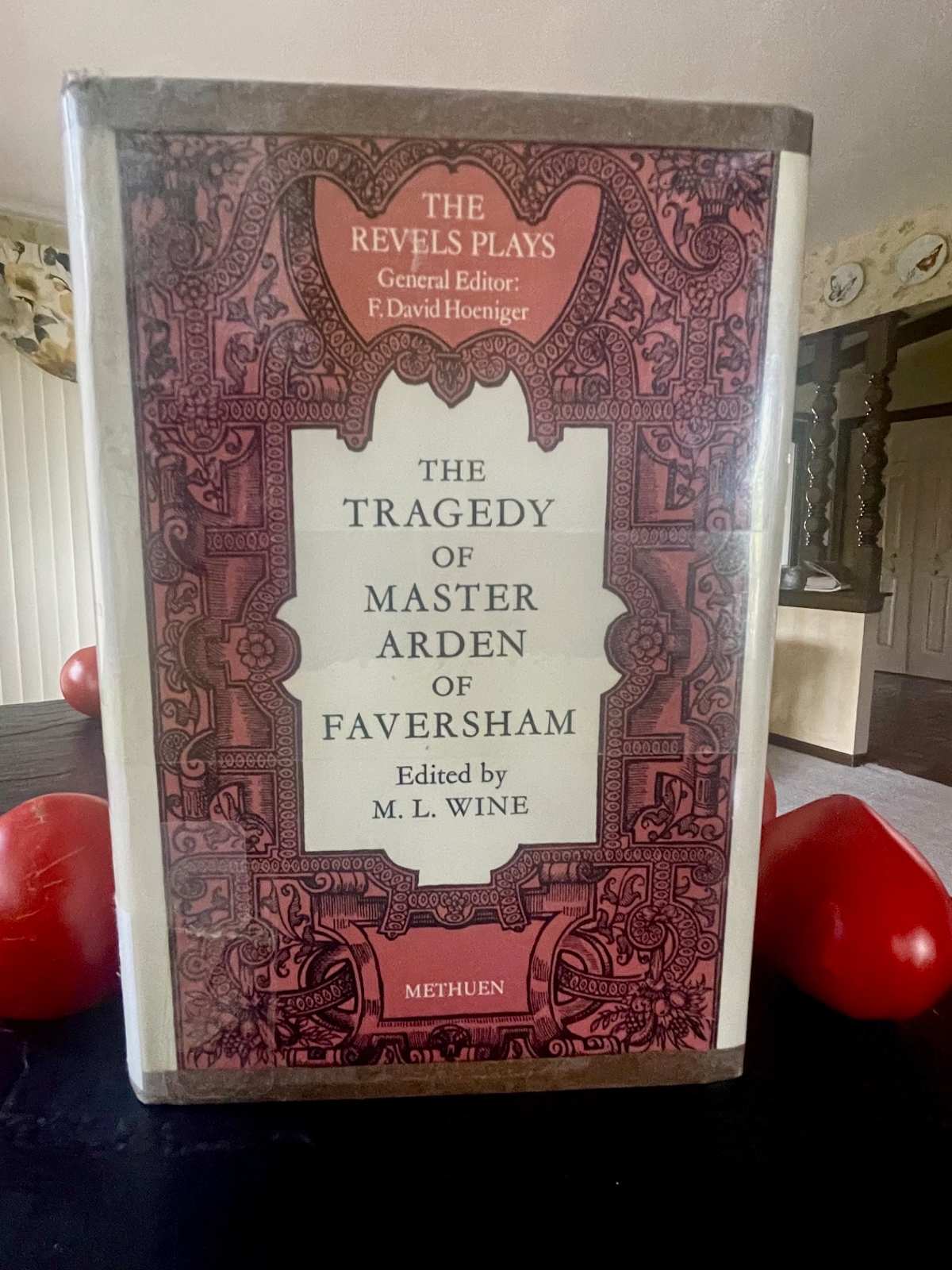

The Tragedy of Master Arden of Faversham, edited by M. L. Wine, was published in 1973, as part of a series known as Revels Plays. At that time, M. L. White was a Professor of English at the University of Illinois (Chicago). In the book, White wrote about a play entitled The tragedie of Arden of Feuersham & blackwill, which was registered in London on April 3, 1592, by the London bookseller Edward White. When the play was initially registered the author of the play was not listed. The author of the play is still not definitively known (more later).

Wine’s book begins with a lengthy Introduction divided into six technical sections: Text, Sources, Date, Stage History, The Play, and Authorship. Wine also includes a version of the play in its entirety; and three supporting appendixes, including one entitled, “The Source of Arden of Faversham in Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland”.

Wine noted that; “The annals of English drama frequently accord Arden of Faversham the distinction of establishing the genre of domestic homiletic tragedy.” The play, based on a true event, tells the story of Alice Arden and her lover Mosby, as they murdered Alice’s husband Thomas Arden (a Gentleman of Faversham) with the assistance of two villains named Black Will and Shakebag.

Wine did a good job presenting the background and history of the play; and the play itself is entertaining. I recommend the book to anybody interested in the history of Elizabethan drama and/or interested in a somewhat comedic domestic homiletic tragedy.

My Interest in Arden of Faversham

I first read this book when researching my book The Polesworth Circle: The Education of William Shakespeare. During my research, I discovered that two of my ancestors employed Raphael Holinshed (the source of the play) as the steward of their manor at Bramcote, Warwickshire, England. During my research, I also discovered a possible connection between my Burdetts and a literary salon called the Polesworth Circle, where a young William Shakespeare was educated (per Arthur Gray in A Chapter in the Early Life of Shakespeare).

I also discovered that Holinshed was the source (or a source) for seven of Shakespeare’s plays. Per Jesse M. Lander, in The 2010 World Book Encyclopedia Yearbook, they were (in the order they were thought to have been performed): Henry VI, Parts I, II, and III (1589-92); Richard III (1592-4); King John (1594); Henry V (1599); King Lear (1605); Macbeth (1606), and Henry VIII (1613). Arden of Faversham, registered in 1592, was thus written about the same time that Shakespeare’s early plays, such as Richard III, were starting to be performed. After considering the above list, I concluded that Shakespeare had more than a casual connection to Raphael Holinshed.

The ”Authorship” of Arden of Faversham

Wine used twelve pages to review the “authorship” of Arden of Faversham. Early in this section he wrote, “No conclusive external evidence exists to support the claim on any known writer of the period, and the deductions from internal evidence alone have never completely satisfied all readers.” After further analysis, Wine wrote, “of all the cases presented for and against various known playwrights that for Shakespeare emerges as the strongest.”

Wine noted that Edward Jacob, who edited the play in 1770, thought it was likely that Shakespeare was drawn to the play because “Arden” was his mother’s maiden name. I believe (speculate) that Shakespeare wrote the play because of his relationship with “The Polesworth Circle,” my Burdett ancestors (who knew or knew of Thomas Arden), and Rhaphael Holinshed. My book The Polesworth Circle develops the above theories and connections; I will not attempt to restate them now. I will, however, further develop a few points that are related to Arden of Faversham and my Burdett ancestors.

The Burdett Connections to Thomas Arden and Arden of Faversham

Very simply, my ancestors Robert Burdett (1507-1547) and Thomas Burdett (1532-1591) employed Raphael Holinshed. He was the steward of their manor (Bramcote). They also supported his writing; they were his literary patrons. Via their library at Bramcote and their money they supported Holinshed. And, in deference to his patrons, Holinshed tried to please the Burdetts. Holinshed reluctantly wrote about the murder of Thomas Arden because the Burdett’s wanted him to. Robert Burdett and Thomas Arden were in the English House of Commons together, and the Burdett’s, for whatever reason, wanted Arden’s story told. Likewise, as noted in my book, Holinshed’s tales concerning the Burdett family in Chronicles were consistent with the narrative that the family wanted told.

In my book (historical play) I speculated that Holinshed tutored William Shakespeare – taught him the art of storytelling and developed Shakespeare’s interest in history. I further speculated that Holinshed encouraged Shakespeare to write a play about Thomas Arden and further encouraged Shakespeare to write favorably of the Burdetts.

Both Holinshed (in Chronicles) and Shakespeare (in Richard III, Act III, scene V, verses 74-78, “... Tell them how Edward put to death a citizen ...”) wrote about Thomas Burdet. Shakespeare could have used Burdet’s name (Hall and More did), and he could have gotten into some of the more lurid details that Holinshed had tip-toed around in Chronicles, but he didn’t.

Black Will and Shakebag

A couple of other observations involving Arden of Faversham, Richard III, and a third play The True Tragedy of Richard the Third (a ‘bad quarto’, registered and printed in 1594, author also unknown).

All three plays feature a pair of murderers. As previously noted, they were named Black Will and Shakebag in Arden of Faversham. In Richard III, the murderers of George, Duke of Clarence (Thomas Burdet’s friend) were simply identified as “Murderer 1” and “Murderer 2.” Both sets of murderers were somewhat comedic in their approach to their crimes.

Wine, in his book (page xlvi) notes that, “... Black Will’s name [was later introduced] in The True Tragedy of Richard the Third ... for no reason, apparently, other than to recall this popular figure.” Wine, further noted M. P. Jackson’s observation that, “The braggadocio of Will in The True Tragedy of Richard III is very similar to that of Will in Arden and there are even verbal parallels.”

Thus, three plays, all written about the same time, feature comedic murderers; but the author of only one of the plays is known for sure (as if anything regarding Shakespeare is known for sure).

Then again, Shakespeare, the most original, distinctive, and creative writer of that time, may have been attracted to the story of Arden simply because of the names of the murderers. In the dialogue that he wrote, he made those murderers comedic and boastful. What else would you expect of (Black Will Shakebagspeare)?